For centuries, the quiet Gulf country of Oman was a center of Indian Ocean trade. Now, flush with oil money and with an eye toward a more sustainable future, it is embracing tourism. Saki Knafo explores its ancient towns, vast deserts, and winding, wild coastline and finds a proud nation at the crossroads.

When I told people I was going to Oman, a small country on the Arabian Sea, I was mostly met with blank stares. O-what? Where was it exactly? Was it safe to visit? To be honest, though I’ve traveled to the Middle East many times, I’d barely heard of it myself. In a turbulent region, it is an oasis of calm, and therefore not the type of place you tend to read about in the news.

Of course, that’s exactly why more people should know about it. That, and the red-sand deserts, the beaches strewn with shells and coral, the mountains where farmers grow peaches and pomegranates on terraces carved into the rock.

And the people. When you’re traveling, as I was, between luxury hotels where staff members beam at you warmly every evening, it’s easy to feel like whatever country you’re visiting is the most hospitable country in the world. But in the case of Oman, that might actually be true. Perfect strangers stop you on the street and invite you into their homes.

My introduction to Oman was Muscat, the ancient seaside capital. Walid, my guide and driver for most of the week, met me at Muscat International Airport’s sleek new passenger terminal—recently opened to accommodate an increasing flow of visitors. “You’re not going to see anybody unhappy in this country,” he said, as we glided down a traffic-free highway lined with brilliant whitewashed houses. “You put a foot in this country, you are going to be happy.” Walid, it turned out, was given to declarations like this—sunny assertions of national pride that sounded as though they’d been cribbed from a tourist brochure. At first, I suspected he secretly worked for the government, so over-the-top were his outbursts of patriotic exuberance. Then I met another Omani, and another, and heard them all speak of their country in the same euphoric tone, and I had to concede that the enthusiasm was real.

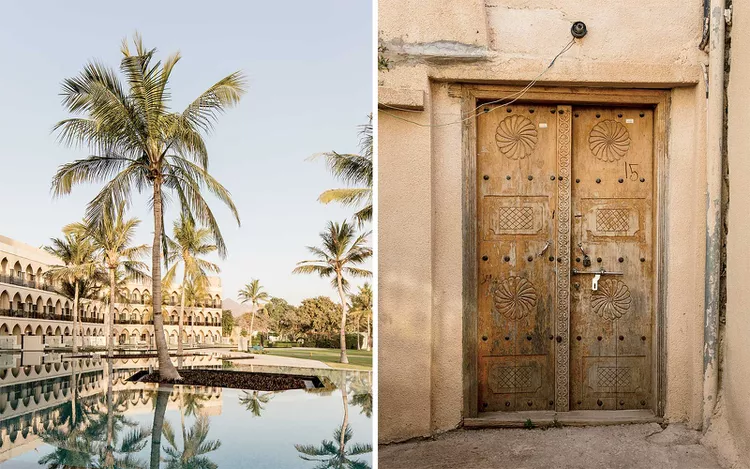

When we arrived at the hotel, a Ritz-Carlton property called Al Bustan Palace, I discovered it was an actual palace, the sweeping marble plaza out front leading to an atrium with a soaring dome, nearly every inch of which had been chiseled into a swirling Arabic design. The young man at the check-in desk told me that “his majesty” built it only a few decades ago, originally for a summit of the Gulf Cooperation Council.

His majesty was Sultan Qaboos bin Said al Said, the intensely private absolutist monarch with the trim white beard who was peering at me from a portrait hanging in the lobby—one of countless similar portraits hanging in homes and businesses throughout Oman. Qaboos has run the country for almost 50 years, and, however autocratic his rule may be, many Omanis credit their country’s peacefulness and stability to his leadership. Next door, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates are blockading Qatar, because Qatar is sort of aligned with Iran, which is arming the rebel forces in Yemen and trading the usual threats with Israel. And Oman, somehow, is friendly with all of those countries while managing to maintain its own comparatively peaceful bubble. Friendliness runs deep in the Omani character.

5 Things to Do in Oman

The next morning, Walid took me on a tour of the city of 1.3 million. As we passed rows of stately houses bedecked with traditional Omani turrets, Walid told me that they’d all been built in the past 20 years. I asked what I would have seen if I’d visited before they went up. Smaller houses? “Desert,” he said with a laugh. A few decades ago, Muscat was a fraction of its current size, a small port town with an outsize role in international affairs. Located near the gateway to the Persian Gulf, it has for centuries been the hub of a network of trading routes stretching from India in the east to Zanzibar, off the coast of Africa, in the west, and the city remains a place of many cultures—facing out toward the Indian Ocean as much as it looks inward to the rest of Arabia. Walid told me that his ancestors came from Balochistan, a state in what is now Pakistan that, situated across the Gulf of Oman, has ancient ties to the sultanate. In the fish market by the port, where he showed me around, I heard workers banter in Swahili as they negotiated with customers over 50-pound tunas laid out on tables in shimmery rafts.

Like many who visit Oman, I arrived via a transfer in Dubai, and I’d wondered if Muscat would resemble that hypermodern phantasmagoria of skyscrapers next door. The two towns do have certain quirks in common and both have grown exponentially in recent decades, their economies borne aloft by a tide of oil wealth. But their differences are more striking.

To begin with, there aren’t any skyscrapers in Muscat—the law prohibits them. If Dubai’s architecture strains toward a vision of the chrome-and-glass future, then Muscat’s buildings, even the new ones, gaze backward toward a crenellated sandstone past. Nowhere is this yearning displayed more clearly than at the Sultan Qaboos Grand Mosque, a sprawling dreamscape of Indian stone and Persian carpet built at the end of the 20th century to look like a jewel of the old Islamic empire.

As I passed through the gate and approached the bright, soaring complex, the bone-white minaret and golden dome were reflected in the mirror of polished courtyard beneath my feet. “What do you think when you see this?” asked Walid, once we’d taken off our shoes and entered the main prayer hall. It was a rhetorical question, and he answered it himself: “Wow.” Wandering the echoing hall in my socks, I could only nod in agreement. The place was vast. (Worshipper capacity: 20,000. Knots in the carpet, which took four years to weave: 1.7 billion.) In the public information office, employees fed us halwa, a saffron-scented pudding, spooning the dessert directly into our hands while talking up the virtues of religious tolerance. “We don’t believe in fanaticism,” said an old man with a long white beard who sidled up to me on a couch. “Oman is always peaceful. We want this peace to go all around the earth.”

From the mosque, it’s a short drive (down Sultan Qaboos Street) to one of the classical-music-loving sultan’s other projects: the Royal Opera House. One of just four opera houses in the Middle East, it opened in 2011 with a production of “Turandot” conducted by Plácido Domingo. If you visit during the day, when no one is performing, you can pay three rials (about eight dollars) to take a tour and admire the musical instruments on display in the lobby. Oman has a rich musical tradition, shaped by its history as a trading center, but the exhibition didn’t feature any African-influenced Omani drums. Instead, I found myself gazing at artifacts of the royal courts of old Europe—lyres and flutes and an adorable pocket-size violin called a pochette. It wasn’t long ago that Western powers loaded their museums with treasures purchased or plundered from places like Oman. How better to signal Muscat’s ascendancy and global ambitions than by charging visitors to contemplate relics of Western cultural history?

On my third day, Walid drove me down the coast to Sur, a city famous for building dhows—the wooden sailboats with long, curved prows that carried slaves and spices across the Indian Ocean for centuries. We visited a factory where the ships are still built, now as pleasure crafts for wealthy visitors from the Gulf. A giant boat was propped up outside on wooden beams. South Asian workers were sawing planks in the hot afternoon sun. Afterward, we stopped at a no-frills restaurant, where most of the diners were reclining on carpets, to order a traditional Omani lunch: a whole red snapper rubbed in curry, grilled and served over a biryani studded with cardamom pods—the Indian Ocean on a plate.

Later that day, after driving through the rocky Hajar mountain range that runs up and down Oman’s northern coast, I climbed onto the back of a camel named Karisma (after the Indian movie star Karisma Kapoor) and set off across a rippling expanse of dunes that looked exactly like every Westerner’s Arabian desert fantasy. I was at the edge of the Wahiba Sands, following a turbaned guide named Ali toward my lodging for the night, a place half an hour into the desert that had been described to me as a Bedouin camp. I was aware that the Bedouin don’t always get around on camels anymore (Toyota trucks are the transportation of choice), but there was nothing inauthentic about the awesome scale of the emptiness around me or the sting of the sand blowing into my face, so I was eager to talk to Ali—to hear his stories about Bedouin life, Toyotas and all.

“I am not Bedouin,” said Ali, once we’d disembarked from the camels.

Ali and I spent the evening talking outside my luxurious tent, pitched by the camping company Canvas Club, which was big enough for a king-size bed and lined with Oriental cushions, like something a high-ranking British army officer might have slept in during an Arabian campaign. He had an air of cheerful formality, but he was also very candid. He told me about the village where he grew up, and about the drought that killed his family’s livestock—how it forced him to leave his home and seek a living in Dubai, where he got his first job dressing up as a Bedouin for tourists. There were “floodlights, and DJs, and quad bikes, and dune buggies, and many kinds of luxury cars,” he said, with an amused grin. “In the middle of the desert.” He liked it better here in Oman, he said, where the desert was quiet and the night was full of stars.

Early in the morning, while it was still dark, I left my tent to climb the dunes. The sand was cold on my bare feet, and as the sky began to lighten on the horizon, I noticed small, crisscrossing, stitch-like tracks, which Ali later told me had been made by beetles. I scaled what I thought was the tallest dune, but as I scrambled to the crest, I saw a taller one beyond it, and so I climbed that one, too, and the one after that, and so on, until I’d lost sight of the tent, and then I sat in the sand and watched the sun come up and turn the desert gold and rose and lavender and red. After following my footprints back to camp, I found Ali bending over a fire made from the dry brush scattered among the dunes, frying an omelette, which I washed down with coffee from a French press at a little restaurant table set up in the sand. In the end, my desert adventure hadn’t taught me much about Bedouin life, but it had given me a glimpse into another side of the country. There are more than 2 million people in Oman like Ali—migrants from Pakistan, India, Bangladesh, and the Philippines, who have moved there hoping to save enough money to put their children through school or pay for generators or wells back home—and their stories are just as important for understanding modern life there.

When you think of Arabia, you think of the desert. But Oman also has mountains—majestic, rust-colored peaks and mesas where, for thousands of years, farmers have been growing apricots, walnuts, olives, roses, grapes, and pomegranates on narrow ledges carved out of the cliffs. These plots are irrigated by a method called falaj. Once a day, special officials called areefs open a gate in a stone cistern at the top of the mountain, allowing just enough water to travel down the mountainside through a system of narrow channels chiseled into the rock.

I toured some of these cliff-side gardens while staying at Anantara Al Jabal Al Akhdar, a hotel that sits upon one of Oman’s tallest mountains. The upscale chain that runs it has outposts in secluded spots all around the world and, like many of the best hotel brands these days, designs its properties to reflect and celebrate their natural and cultural surroundings. On Jabal Akhdar, also known as the “Green Mountain,” that means planting the resort’s Edenic grounds with hundreds of native trees and herbs—figs, plums, lemons, thyme—and rivulets modeled after the falaj system running along the walkways. But while the traditional structures that inspired these features allowed people to eke out a living in an extremely harsh environment, the resort was designed for maximum ease and indulgence. I don’t mean your infinity pools and your spa treatments and your international smorgasbords, though it has those, of course; I’m talking about a staff that was so friendly and gracious, so plainly delighted by my presence, I nearly fooled myself into thinking I was just that charming.

One afternoon, a guide from the hotel took me and a Belgian family on a tour of the villages built into the mountainside. It was a bright, cool day, as was every day I spent up in the mountains, bright enough that it called for sunglasses and cool enough that I was glad I’d brought a sweater. The rough stone houses were built one above the other, so that if I stood at the entrance of one, I found myself looking down at the roof of a neighbor; the streets were barely wide enough to fit a donkey cart, and so steep they were mostly stairs. Down one alleyway, I saw a gaggle of kids kicking around a soccer ball, and I wondered where they would ever find a field flat and wide enough for a normal game. Later, one of the villagers told me that, when he and his friends were young, they’d hike with their ball 45 minutes up the mountain.

At one point on the walk, the guide pointed out that many of the terraced gardens were barren. Starting about a decade ago, she explained, the rains began to fall in the mountains less often, and a tide of drought began creeping up the mountainside, claiming another three or four terraces each year. The sultan, she said, has been building a pipeline that should carry desalinated seawater to the villages, but it’s anyone’s guess whether this will work well enough to allow people to continue cultivating delicate crops like peaches and grapes; in the meantime, the hotel has to truck 50,000 gallons up the mountain every day for its guests.

Hearing this, I thought about Oman’s complicated relationship to oil. On the one hand, oil is the lifeblood of the country’s economy. On the other, it’s making parts of the world hotter and drier, and in Oman the effects have been particularly acute—it is, after all, one of the world’s hottest, driest places to begin with. I posed a hypothetical scenario to the villager who told me about playing soccer on top of the mesa. Say he could undo all the damage caused by climate change, saving the orchards that his family had tended for generations, but only if it meant giving up all of the comforts and conveniences that have come with the oil economy—the roads, the cars, the air-conditioning, the hospitals, the universities. He said he’d have to go with the comforts (“I am too used to this”), but, like many in Oman, he knew that the country would have to wean itself off oil eventually, and he hoped that the growing tourism industry would help fill the void. He himself had gone to engineering school in hopes of working in the oil fields, but now, with oil prices falling and the industry shrinking, he was working at the hotel, leading rope-course adventures on the cliffs where he’d grown up. “I like it,” he said. “The world is coming to us.”

My final stop in Oman was the Musandam Peninsula, which juts northeast into the Strait of Hormuz toward the Iranian coast, forming a bottleneck that ships have to pass through as they travel between the Indian Ocean and the Persian Gulf. Getting there is an adventure in itself. Musandam is completely cut off from the rest of Oman, the way Alaska is cut off from the Lower 48. I had to fly from Muscat back to Dubai, and then take a cab two hours through flat urban sprawl before arriving at the Musandam border. As soon as we crossed back over into Oman, craggy mountains began to rise all around the car and a hush fell over the empty road. The noise and traffic of Dubai and its suburbs seemed a world away.

I spent the next three days at Six Senses Zighy Bay, a resort nestled between Musandam’s mountains and the Gulf of Oman, on a secluded crescent of beach scattered with tropical shells. A few minutes’ walk down the shore was Zaghi, a fishing village where people had lived largely in isolation from the modern world until the resort arrived 11 years ago—bringing with it, among other things, a road and electricity. The resort was an opulent mirror of the village, its villas made of palm thatch, stone, and mud. Pathways of raked sand meandered between the buildings and pools and the organic garden, where I walked among the bees and butterflies, tearing off leaves of Indian basil, and za’tar, from which the famous spice blend is made, and dozens of other herbs and vegetables.

Holding them up to my nose, I thought about how the chef had worked them into my seven-course dinner the night before. That evening, I’d climbed more than a hundred stone steps up the side of a mountain to an open-air restaurant overlooking the bay, where I feasted while gazing at the twinkling lights of the container ships out at sea. I had ravioli filled with a velvety mousse of quail confit, a lobster tail bathed in an orange emulsion, and octopus that had spent the day sous vide. These recipes weren’t exactly Omani standards, but the local ingredients, presented in a style adopted from the West, carried on a sort of tradition. Omani cuisine has always been influenced by the many different kinds of people who have passed through the country—the spice merchants with their sacks of curry from India and saffron from Persia, the itinerant fishermen with their hauls of kingfish and tuna, the desert-dwelling herders, who slow-cook goat and lamb in ovens dug into the sand.

One hot and clear-skied afternoon, I met an affable and confident Bulgarian paraglider pilot. (His confidence was key to my sense of well-being, because I was about to put my life in his hands.) A driver took us up a winding road into the mountains and parked near the edge of a cliff facing the sea. The pilot dragged his folded paraglider out of the car and buckled both of us into our harnesses, pulling at the ropes until the wind filled the sails. We ran together toward the edge of the cliff and jumped.

The moment I leapt, I felt the harness catch my weight, and I relaxed into the seat as the pilot steered us higher and higher on the currents of air, the wind rushing past. We soared up and over a jagged ridge, blades of rock pointing up at us like pikes on a castle wall. The pilot dipped into a break in the cliffs and turned a few exhilarating loops before flying back out toward the bay. I could see the thatched roofs of the villas down below, and the fishing village with its mud-domed mosque—the new and the old, the luxurious and humble, side by side. Oman, in all its rugged beauty, was spread out beneath my dangling feet. Slowly we began our descent, spiraling downward in languorous loops until we were running down the soft sandy beach toward the sea.

City, Desert, Mountains, Beach

Oman is a place of diverse landscapes—give yourself a week or more to get a taste of several.

Getting There

The best option is to connect through a neighboring Gulf city like Doha or Dubai, both just a 90-minute hop away from Muscat. U.S. citizens should apply for an e-visa in advance.

Muscat

The seaside Al Bustan Palace, a Ritz-Carlton Hotel recently unveiled a renovation that emphasizes traditional Omani design. Other world-class openings around the capital include the Kempinski Hotel Muscat and the Jumeirah Muscat Bay, coming later this year.

Wahiba Sands

This desert region, a few hours southeast of Muscat, is closer (and more hospitable) than the better-known Empty Quarter, the unforgiving expanse that covers a fourth of the Arabian Peninsula. Canvas Club can set you up in a luxe, Bedouin-style camp under the stars.

Jabal Akhdar

From Wahiba, a three-hour drive northwest takes you through hillside villages and date plantations. The newest property in the area is the striking, 115-room Anantara Al Jabal Al Akhdar, the highest-elevation resort in Arabia. Another excellent option is Alila Jabal Akhdar, the first luxury resort in the area—which we named to our It List of best new hotels in 2015.

Musandam Peninsula

About a five-hour drive northwest from Muscat, this exclave is separated from the rest of Oman by the eastern United Arab Emirates; avoid multiple land border crossings by flying to Dubai and driving from there. The luxury resort Six Senses Zighy Bay makes the detour worth it.

A version of this story first appeared in the July 2019 issue of GoTravelDaily under the headline The Edge of Arabia. Al Bustan Palace, Anantara Al Jabal Al Akhdar, Canvas Club, Six Senses Zighy Bay, and Zahara Tours provided support for the reporting of this story.