The Journey of Abongi Gael Bokongo: From War to Adventure

The “Great African War” was a difficult chapter for the Congo-Kinshasa. For two decades, the now Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) was torn apart by endless political and military conflicts. The conflicts not only provoked a spiral of violence in the country and obstructed political and economic development but also greatly contributed to the destruction of society and the collapse of the Congolese state. Traveler Abongi Gael Bokongo shares how the civil war sparked his interest in travel.

Gunshots, Loud Screams, Soldiers

Living in my 12-year-old world, I was oblivious to the brewing war. It was only through big ears – listening to the conversations of grownups – that I slowly grasped the reality. Every morning, my friends and I gingerly stepped over spent bullet shells during our daily soccer games on the dusty streets of Limété in Kinshasa.

Like a low-hanging gray cloud, there was an atmospheric change. Parents spoke in hushed tones late at night and cautioned their children to avoid staying outside for any length of time; the usual family visits were curtailed.

While my dad appeared calm and in charge, as an adult, I now understand he was just as fearful as everyone else. His silent strength made my siblings and me feel safe, and we knew that if dad was around, everything would be OK. He had the right words, perfect tone, and disposition that would put all worries at ease.

However, something was off.

Conversations between my parents took on a new sense of urgency, and tones changed. Although they tried to keep their arguments to intense whispers, again my “big ears” picked up bits and pieces.

My mom became sterner. She mixed words between French, Lingala, and Swahili due to the trepidation she felt but couldn’t openly express. In her quest to keep things as “normal” as possible for us, she internalized her fear and apprehension, which only surfaced during infrequent angry exchanges with my dad.

My brothers and I received a host of new warnings about going outside to play, while my sister wasn’t allowed out at all. My parents’ fear of her being kidnapped and raped by rebels meant she was on permanent lockdown. This was my introduction to the evil acts against humanity.

The children of Limété were given “crash courses” on survival tactics in the event of a shooting. The sound of bullets between the rebels and the police gradually became as common as a summer hit that looped over the radio.

The Depth of the Congolese Spirit

Though war had not officially been declared, terror was present in our daily lives. Despite everything, the Congolese exhibited great courage and strength in their fight for survival. In a cruel environment, the gestures of humanity and heroism doubled; people banded together like never before and a community spirit evolved to become a comforting weight on all fears.

I remember a neighbor risking his life to save a child from a speeding army truck. Solidarity increased, and strangers came together under the dome of survival. People embraced loved ones because tomorrow was not promised to any of us.

During this tumultuous time, my parents made the decision to act. As I reflect as an adult, I can only imagine how difficult that decision was: telling your children the family was going to flee because of an emerging war.

The Mission

My parents skillfully plotted a brilliant scheme. My mom, ever the creative one, presented this entire relocation as an adventure. We were embarking on an escapade like Indiana Jones. She spent hours passionately describing scenes from the Indiana Jones sagas, captivating my siblings and me.

My dad supported everything and “sweetened the pot” by promising a Holy Grail at the journey’s end. As children who were huge fans of rugged adventures, this was more than we could imagine.

We were ready to go.

I remember discussing the upcoming trip with my brothers and recounting our favorite Indiana Jones scenes. My favorite was the high-speed mine cart chase from Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom.

Time to Go

Everything came to a head at dawn on a Tuesday in mid-October when my siblings and I were awakened with the quiet but firm words, “It’s time to leave.”

We jumped out of bed and hurriedly got dressed, all excited for our adventure. My parents were calm; there was never any sense that this journey would define our lives.

Everything went smoothly; our parents had prepared ahead of time. Luggage was packed and ready, and kindness met firmness; it was clearly not the time to “horse around.” Just as the sun broke the gray sky, we piled into my dad’s friend’s car and headed for the port of Matadi, located on the left bank of the Congo River, to reach Congo Brazzaville.

Everything happened so quickly. I never got a chance to bid goodbye to my friends or share the news about my exciting adventure.

The Journey Begins

Despite the many large boats that seemed safe, we climbed aboard a small, rickety vessel. This old boat, blistered by the sun, looked like it had seen better days. The chipped green paint unveiled the initial brown color of the wood. Safe was not the first word that came to mind once all six of us were on board. Though I never feared water, the boat’s instability did not inspire peace.

We were joined by another family, a couple with two young daughters, probably around five and three years old. I figured they might also be playing Indiana Jones.

The reality, however, was different.

The same worry lines etched on my mom’s face mirrored those of the young mother, emphasizing that we were not the only ones fleeing. This scenario encapsulated the national feeling and the difficult decisions every family was making at that time. Yet, the intrigue of our trip overshadowed any internal panic.

Upon reaching Brazzaville, the capital of the Republic of Congo, I remember seeing my father pay the boatmate. The boatmate said in Lingala: “Zambé, Apapolissa bino, bo kendé bien,” which means: “May God keep you on your journey.”

A friend of my mother was there to pick us up. They embraced, and for a moment, my mother let her guard down and laughed. Their conversation fluctuated between excited tones and somber whispers, a testament to the constant worry permeating the atmosphere.

Separated by a river, Congo Brazzaville had no feelings of insecurity related to the war—none that I felt at least. People moved around freely, and children played without fear. The native language varied, and so did the food. The smell of street dust was unique. This was not a culture shock but rather an observation of how I was no longer home.

We stayed at a hotel with a pool, sheer bliss for my siblings and me. Our stopover lasted just three days as my father’s ultimate plan was to reach Paris, where many of our family members lived. Thanks to my grandfather’s relationship with the French embassy, we secured visas.

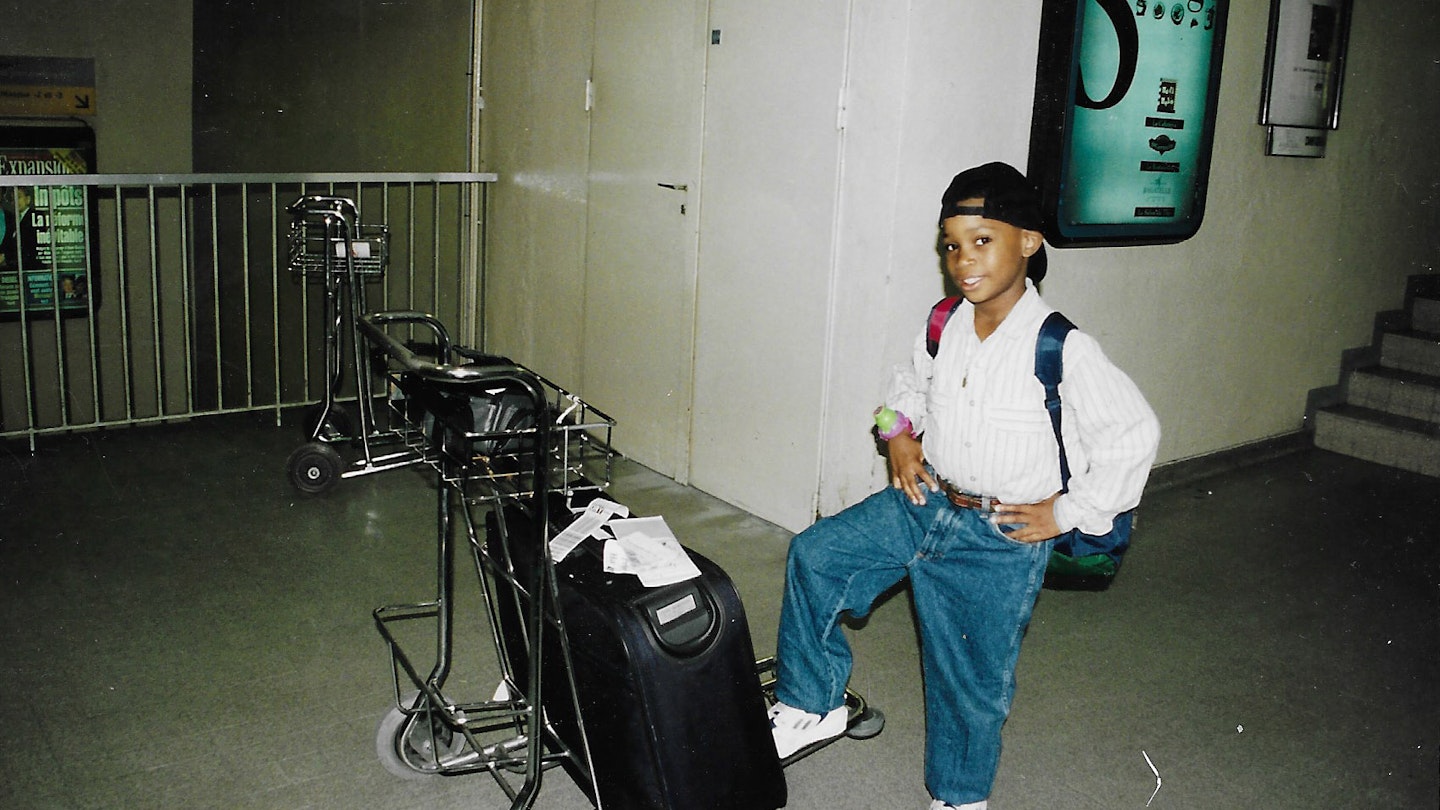

A Long Way from Home

Our first flight wasn’t to Paris, however; it was to Morocco, specifically to the city of Rabat. At the time, direct flights to Europe were extremely expensive.

We knew no one in the city, and my mother, after hearing horror stories about the treatment of black people from her friends, feared for our family. Although still in Africa, Rabat felt like new territory, and I had no benchmark for comparison.

People in long, loose-fitting unisex outer robes with full sleeves called djellaba filled the souks where I would go shopping.

The food was incomparable. I fell in love with chorba, a Moroccan soup with vegetables and meat. The tea was flavorful and rich in sugar, delighting my young taste buds.

The residents spoke louder than I was used to; if unfamiliar with the culture, one might think everyone was arguing. I truly felt like Indiana Jones, discovering new things and adapting to my new environment.

For a whole week, my dad used the limited Arabic he had learned so people wouldn’t think of him as a tourist. Without saying a word, he showed me that the first connection anyone can have to another culture is putting in the effort to learn their language.

Nevertheless, I still missed my home, despite its situation. My father reminded me that this was the last step before our Holy Grail. To him, the Holy Grail represented stability and a better future for the family in Europe.

After a final flight to Paris, we had officially left the Congo and its war behind. We accomplished the mission. Although I was happy to be in a new environment, I felt a bit confused after a couple of weeks in Paris.

Without that mission ahead of us, I felt lost. I asked my dad what we were supposed to do now that we made it. With his calm tone, he explained that this was our home now, and we had to be grateful for our new life. We were fortunate to have a fresh start, and many didn’t have that same chance.

He reassured me not to be saddened by not saying goodbye to some friends because, much like Indiana Jones, I would find my way back when the time was right. He reminded me that we had embarked on an adventure like no other.

Fostering a Love of Travel

That journey, born out of necessity, ignited a thirst for exploration and adventure that defines who I am today. I took my first solo trip around the age of 14, visiting family across Europe. I studied abroad in the US and continued to travel and explore.

This passion led to jobs prioritizing travel, including my role as a commodities gas analyst and now as a travel content creator for my marketing company – Eyestell. Every time I’m introduced to new traditions or try new foods, it brings me back to that 12-year-old boy who embarked on the biggest adventure of his life.

The excitement for experiencing new cultures never waned; I now share my passion with my 7-year-old daughter, Deϊyna, who has inherited a thirst for adventure. Together, we have visited over 30 countries across four continents. Deϊyna’s passion for traveling and discovering surpasses my own imagination.