1. Introduction

Athens has evolved into a vibrant cultural hub, blending its ancient history with a flourishing contemporary art scene. This article explores the exciting developments within the city, highlighting key neighborhoods and artistic inspirations.

In the Greek capital, ancient history is everywhere you look. However, these days, the city is also home to boundary-pushing art.

A passerby might have mistaken it for a wedding feast. In Metaxourgio, a formerly industrial neighborhood of Athens, a crowd of boisterous Greeks had spilled onto the street and were squeezing around rows of long tables arranged end to end. The air was filled with the scent of lamb being roasted on an open grill. But rather than someone’s nuptials, this was in fact an exhibition opening at a progressive contemporary art gallery, the Breeder. Housed in a renovated ice cream factory, it was heralded by a sleek (and spotless) white façade. A vast iron portal opened to reveal a regal interior with organic curves.

On the ground floor, the artist Andreas Lolis showed me his striking sculptures. At first glance, they looked like blank canvases that had suffered delicate cuts, but they were actually crafted from that most traditional of Greek materials: marble. “I found inspiration from Henry Moore and Lucio Fontana,” Lolis explained, referring to the British and Argentine-Italian artists. “They both tested the boundaries of what can be achieved within their chosen forms.”

The Breeder is just one example of Athens’s revitalized culture scene, which is thriving despite a series of disasters that would have crushed the spirit of a less resilient city. The Greek capital is still recovering from the economic turmoil that began in 2008 — a crisis that led to a series of financial bailouts from other EU member nations, accompanied by austerity measures that infuriated much of the populace. Those struggles were hardly eased by the global pandemic, but they had their benefits, the gallery’s associate director Alkistis Tsampouraki told me: “I worked for seven years in galleries in Mayfair. I came home two years ago, and I thought, What? This is Athens? Artists I knew in London, and even New Yorkers, had suddenly realized that studios could be rented here for 300 euros a month, with a quality of life that is hard to beat.”

In fact, Tsampouraki said, Athens’s volatile history since the crisis is the unlikely key to its revival: “Where there is chaos, there is also creativity.” The city’s popularity with bohemians and its use of derelict urban spaces inspired the phrase “Athens is the new Berlin,” which was coined by a street artist named Cacao Rocks around 2009 and seized upon internationally the next year. Athenians reviled that description — in part because they considered the forced spending cuts demanded by Germany in the EU’s 2010 rescue package brutal and unfair.

Sometime around 2015, Cacao Rocks started daubing walls with THIS IS NOT BERLIN as a form of protest. In 2017, he evolved the sentiment further, coining his most popular and pointed version: ATHENS IS THE NEW ATHENS. But if there is any real comparison, Tsampouraki insisted, it is to New York City in the 1980s: “It was dirty and difficult, but also incredibly creative. It had an energy that was addictive. That’s Athens today.”

I could relate to Tsampouraki’s surprise. Twenty years ago, I spent weeks in Athens to research Pagan Holiday and The Naked Olympics, my two books on the classical Greek world. I love an Acropolis view as much as the next person, but I was forced to agree with the general opinion of the city as a traffic-clogged, unlovable mess to be passed through as quickly as possible on the way to the islands. However, word has been filtering out that Athens is rebounding with a gusto unseen since the days of Plato. Therefore, I decided to make a pilgrimage back to the fountainhead of Western culture. This time, I swore, I would pay little heed to its wealth of ancient ruins and concentrate instead on what has happened in the past few years.

I hopped in a cab from the airport straight to the Shila Hotel. This six-room boutique property is a calm oasis of art and beauty that’s set in a 1920s Neoclassical townhouse in the Kolonaki district, a well-heeled enclave of steep streets at the base of Lycabettus Hill.

Like many businesses that comprise the new Athens vanguard, the Shila deftly balances elements of tradition and modernity, which is a quality that defines many of the city’s best hotels. My suite — called the Dreamers — was decorated with original terrazzo floors, antiques and artisan-made pieces, and contemporary artwork. For me, the true advantage of staying at the Shila was the chance to attend its Social Club, an invitation-only event that has since been relocated to Shila’s sister property, Mona, under the name Club Monamour. It’s a hot ticket for the creative types that have descended on Athens, many of them returning expats like Tsampouraki.

As soon as I had climbed the stairs to the rooftop, where the festivities were being held, I ran into the Shila’s creative director, artist-photographer Eftihia Stefanidi, who moved back from New York to curate the hotel’s art collection. Stefanidi introduced me to the cast of regulars, including her sister Elli (an artist based in New York who returns every summer) and her friend Alexandra Mercuri (a Greek-born designer, freshly back from Paris), who then presented me to her sister Dorotea (a Greek actress and TV host, back from New York), Alexia Kirmitsi (a fashion designer, back from London), and Andreas Lagos (a nomadic chef who advises the new wave of Athenian restaurants and has proselytized on behalf of Greek cuisine in the U.K. and U.S.). Within an hour, I felt like I had met half of Athens, been plied with hot tips on the city, and received enough invitations to dinners and drinks to last me a month.

The Shila Social Club resembled a Greek version of Soho House, but nobody was about to confuse it with London or New York, I realized as I sipped a “Perfect Greek G and T” made from a locally crafted gin called Votanikon, distilled with a variety of endemic herbs — including earthy sideritis and piny mastiha — that “highlight the botanical heritage of Greece,” according to Stefanidi.

Armed with suggestions from my new friends, I was ready to sally forth to explore the “New Athens.” I began with lunch at the city’s first (and only) Japanese-Greek restaurant, Nolan. Only a stone’s throw from noisy Syntagma Square — the official center of Athens, with its pompous Parliament House and formal parks — I savored such cross-cultural delicacies as bean noodles with octopus and kalamata olives.

Today, the city’s allure is the way the centuries blend effortlessly. Young Greeks are beginning to forge a cultural identity that absorbs and builds on ancient Greek culture, as well as the rest of its long and convoluted history.

From there, I bypassed Plaka — the old Turkish quarter where the busy paths to the Acropolis begin — and migrated to the Clumsies, a cocktail lounge set in a cozy town house in the central neighborhood of Psirri. Ranked on the World’s Top 50 Bars list for the past three years, it has become known for its famed Aegean Negroni, which mixes the bar’s own artisanal gin with fennel seeds and exotic Greek liqueurs such as Diktamo into a fluorescent turquoise concoction worthy of the sea it’s named after.

Hesitant to call it a night, I headed to an even newer and more fashionable bar, Santarosa, just north of the city center in Exarcheia, where a perfectly groomed papillon puppy frolicked along the wooden bar beneath abstract paintings, and patrons chain-smoked as if the EU ban on cigarettes indoors had never been enacted. This indifference to the law has made the bar an underground favorite. “How did you hear about it?” Athenians asked me suspiciously later, as if I would expose their secret.

Other once-derelict working-class districts are also gentrifying with dizzying speed. Many roads led me back to Metaxourgio, a name that translates to “silk mill” and harks back to the area’s industrial past. Under the belief that the king of Greece was going to move his palace nearby, aristocrats built grand homes there in the 1830s and invested in a giant shopping center, which was turned into a silk mill when the sovereign later changed his mind. The area fell into decay last century, but has bounced back in the past several years.

“It’s my favorite neighborhood,” explained a street artist known as Rude, who showed me around Metaxourgio one afternoon. The neighborhood certainly encourages the creative use of historic space. We passed one half-ruined, roofless mansion where the interior had been repurposed as a courtyard to house Galiántra, a truck serving contemporary comfort foods like meatballs with creamy tsalafouti cheese, soy-mince stew with cucumber and onions, and tomato and watermelon salad. “No food trucks are allowed on the streets in Athens, so a group of chefs rented a whole house and put one inside,” Rude explained. Just as eccentric is the nearby Latraac, a café with its own skateboard bowl.

Rude wanted to show me the most provocative street art in the city. Since the economic crisis of 2008, painters with names like Ino, Achilles, Exit, Waxhead, Same84, and Simple G have turned the whole of Athens into an open-air canvas, with monumental images taking up the sides of buildings or billboard-size stretches of walls beside busy highways. Rude’s real name, it turned out, is Nikos Tongas. When I asked him how he picked the handle, he shrugged: “I opened up a dictionary and there it was. I liked it because it is only four letters and so easy to write.” His favorite images found across the city included a black-and-white painting of the Mona Lisa’s eyes, positioned above a busy highway. “Can you see the reflections in her pupils?” he asked. One contained an image of a policeman raising a baton, the other a shifty-looking man in a suit. “The two big problems of Greece — police brutality and corrupt politicians.”

It’s said that the contemporary art scene in Athens was kick-started when it cohosted Documenta in 2017 alongside the exhibition’s longtime home of Kassel, Germany. Artists began arriving in droves, while new galleries and museums sprouted in such numbers that in September 2020, the Financial Times hailed Athens as Europe’s hot spot under the headline AN ART CAPITAL RISES. These days, there are so many cultural spaces in Athens that it’s impossible to see them all — at least in one visit.

I bounced from scrappy local outposts like the Breeder to a lavish satellite of the blue-chip gallery Gagosian, which moved into a palatial mansion in Kolonaki in 2020. Its airy parlors displayed the works of Italian maestro Giuseppe Penone, contrasting photographs of his youthful hands with sculptures made from twisting branches that evoke aging veins. At the National Museum of Contemporary Art, which opened in a monolithic new building in the Koukaki neighborhood in 2020, Greek artists are shown alongside global names. I gravitated toward an installation called Acropolis Redux (Director’s Cut) by conceptual artist Kendell Geers. The piece — the name of which is meant to evoke both the ancient fortress complex and Francis Ford Coppola’s war epic — places coiled barbed wire in metal shelves as a commentary on the dangers and violence of modern life.

My favorite venue was Neon, a spectacular art center that debuted in 2021 inside a former tobacco factory in Kolonos, a residential neighborhood in northwest Athens. True to its name, the raw-stone walls of its cavernous atrium were glowing with lines of poetry in blue neon. The work, Waiting for the Barbarians, by the U.S. artist Glenn Ligon, presents nine different translations of a politically charged line from beloved Greek-Egyptian poet C. P. Cavafy’s 1904 masterwork of the same name: “Now what are we going to do without the barbarians? Those people were a kind of solution.” The multiple iterations invite the viewer to contemplate the nuances of language and how the meaning of a phrase can change from tongue to tongue.

As I admired the illuminated poetry on the time-scarred walls, I realized that, after a week of focusing on modern Athens, I was missing the point. Not long ago, cultural critics argued that the city was oppressed by the weight of its illustrious past and that it prized its classical ruins above all else. However, today the city’s allure is the way the centuries blend effortlessly. Young Greeks are beginning to forge a cultural identity that absorbs and builds on ancient Greek culture, as well as the rest of its long and convoluted history, including the long centuries of Turkish rule and the 19th-century independence struggle. Granted, the full expression of that movement is a long way off, but there is already a palpable energy and confidence that feels new.

Some of Athens’s more recent architectural remnants, long ignored, have been converted into theatrical stages for social life. One morning, my artist friends from the Shila Hotel helped me construct a little self-guided tour, starting at T.A.F./the Art Foundation, a multidisciplinary space that occupies a 19th-century Ottoman dwelling that, in the early 1900s, became one of the last tenements for the district’s gas workers and artisans. Hidden down a shoulder-width alley between the antiques stores of the Monastiraki district, it has six small rooms arranged around a verdant patio and a gift shop where young Greek designers sell their jewelry. A short stroll away I found Anänä, a spectacular café in the soaring, light-filled courtyard of a 1936 Art Deco building that has become a favorite hangout for fashionable professionals and serves what may well be the most potent espresso in Greece.

The discoveries became even more exciting at lunchtime when I tracked down an unmarked double door near the central vegetable market and descended worn stone steps into Diporto (9 Sokratous; 30-21-0321-1463), the oldest — and most secret — tavern in the city. As legend has it, the subterranean site was a wine bar in the time of Socrates. Today, the cellar-like space is crowded with wooden wine barrels and rickety tables arranged around a charred metal stove, where battered tin pots of food burble. There is no printed menu, but the white-haired chef and owner, Dimitris Kololios, doled out hearty plates of grilled sardines, a bowl of yiouvetsi (orzo cooked with meat in a red sauce), a delectable Greek version of ratatouille, and Moschofilero wine. He then sat down at my table and scribbled on the paper tablecloth “1959” — the year, he explained, that he began working as a waiter in the restaurant before eventually taking the place over about 20 years ago.

That night, I sought out the ultimate in cross-generational entertainment at Café Avissinia. In this beloved institution, hidden down another winding back alley, Athenians of all ages were boozily singing mournful rebetika to an accordion player and occasionally standing up to dance. “Think of it as the Greek blues,” explained the Shila’s Stefanidi, who had joined me for dinner. “It involves charmolypi, the Greek idea of ‘happy-sad.’” To explain, she translated snippets of the song (“Even if my heart really yearns for it, I will never love again”) and showed me how to dance zeibekiko, a slow step performed with the head bowed and arms extended. “My father always said, just pretend you have dropped your keys and are looking for them on the floor.” By midnight, her advice seemed to be working excellently.

The next night I headed to the Stavros Niarchos Foundation Cultural Center, a complex of white structures that loom in Pharaonic splendor over the surrounding gardens and fountains, for a performance of Marina Abramović’s experimental opera 7 Deaths of Maria Callas. In the gorgeous Renzo Piano–designed concert hall, a packed house of well-heeled Athenians laughed and wept at the extravagant life and death of the great Greek diva.

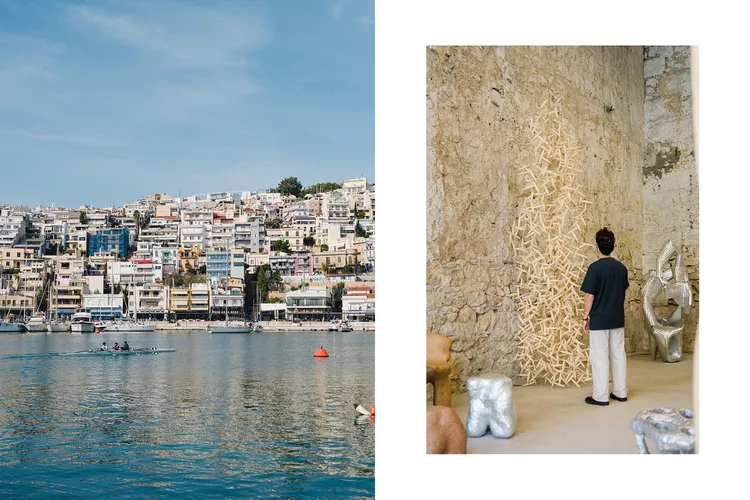

The strands of history came together most seamlessly on my last night, when I took a 15-minute taxi ride to Piraeus, the gritty port district. Back in the fifth century B.C., this was where the ancient Athenian navy was built and headquartered, creating a maritime empire during the golden age of the politician Pericles. In modern times, it became the shipping nexus of the eastern Mediterranean, and today, Stefanidi told me, it’s also one of Europe’s most unlikely art hubs.

Cautiously, I exited my cab on a backstreet, Polidefkous, which was lined with machinery shops and dusty hardware stores selling propellers and boat parts. I quickly spotted the trio of new galleries that have taken the Athenian passion for abandoned work spaces to its most extreme heights. Each one is in a renovated stone warehouse that soars like an industrial cathedral. I started at Rodeo, the oldest of the three, having opened in 2018. The director, Sylvia Kouvali, was showing a bevy of British collectors the gallery’s new acquisitions, including a sculpture of a ghostly silver bush that was secreted behind a noisy electric garage door.

“Greek artists have more international dialogue now,” she said. “They move between MoMA in New York and the Venice Biennale and the Muséed’Orsay in Paris.” Even so, the ancient cultural connection with the Middle East still felt tangible in Piraeus. Kouvali said she had returned to Athens after running a gallery in Istanbul, while the owner of the Carwan Gallery next door had run a pioneering contemporary design gallery in Beirut.

As always in the Greek capital, the most important thing to bring on a gallery hop is a healthy appetite. Next door to Carwan, another warehouse had been taken over by the Paleo Wine Store, where the towering, deadly serious owner Giannis Kaimenakis was putting wooden tables out on the sidewalk. Again, I felt like I was at a wedding party: chatting with the groups who quickly gathered at nearby seats, I settled down to a meal of oven-cooked grouper and risotto while choosing among three dozen fine bottles of wine from some of the Mediterranean’s oldest vineyards, all open and ready to savor. It was the ideal package: contemporary cuisine in a historic setting, a charming local crowd, and good drink.

However, I realized that the ancient Greeks would hardly have been surprised by this modern-day incarnation of their beloved Athens. After all, the gourmandizing philosopher Epicurus came up with an apt slogan for the metropolis 2,500 years ago: “Pleasure is the first good,” he wrote. “It is the beginning of every choice and every aversion.”

Some things, it seems, never change.

A version of this story first appeared in the June 2023 issue of GoTravelDaily under the headline “All New Athens”.