Touring Literary New England

On a pilgrimage to the homes of Alcott, Twain, Melville, Stowe, and Dickinson, we realized the great writers of 19th-century America offer a window on our present and our past.

Shortly after I met my wife, she told me she hoped to one day visit Emily Dickinson’s house in New England. She was working at a publishing house in Paris’s 14th Arrondissement, across the street from Montparnasse Cemetery, where some of France’s most important writers—Baudelaire, Duras, Sartre, and Beauvoir, among others—are buried. As my wife explained, it’s a common belief in France that you can understand a country through its authors.

By the time we began to plan our trip to Dickinson’s home, we had been married for 11 years and had two sons, ages 9 and 10. After spending five years in Paris and six in New York City, we had recently moved to the Hudson Valley and expanded our literary loop east to Hartford, Connecticut; northeast to Concord, Massachusetts; and ultimately back west, to the towns in the Berkshire Mountains. It was the only family trip we would take that summer; the pandemic had rendered most of the country off-limits, and our afternoons and evenings had become devoted to reading about and watching the protests against racism and police brutality flaring up across the country.

Before leaving, my wife and I tried to prepare our sons. We painted quotes from Dickinson’s poems on our pandemic rock garden, downloaded an audiobook of Moby-Dick, returned to our favorite Edith Wharton novels, and watched Greta Gerwig’s 2019 version of Little Women. The night before our departure, our oldest son expressed reservations about visiting old homes no one lived in. My wife explained that the tour was a way to understand what was happening to the country now.

“But the writers are all dead,” my son observed.

“Yes, but we still read their books,” my wife replied.

“So… Are the houses haunted?” he questioned.

It was too good an opportunity to pass up. “Yes,” we told him. “The houses are definitely haunted.”

On the morning we left to visit Mark Twain’s and Harriet Beecher Stowe’s homes in Hartford, Connecticut, we watched an episode of The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, a Japanese anime series from 1980. While reminiscing about the show, we noticed the complex issues of race raised by Twain’s work had been oversimplified, resulting in an even more racist portrayal in the animated version. Consequently, we turned off the computer. Our youngest son asked why, and I mentioned the complications of history.

Some of the conflict in how we approach the past was on display at the Stowe and Twain homes, where two of America’s most famous writers lived within shouting distance of each other in a bucolic, wealthy enclave. Compared to Twain’s sprawling mansion, which sits on one side of an open lawn, Stowe’s cottage-style home comes off as almost self-consciously discreet.

As soon as we entered, my sons were surprised to find familiar faces adorning the walls—President Obama, James Baldwin, Frederick Douglass, and Laura Bush—along with quotes praising or criticizing the legacy of Uncle Tom’s Cabin Stowe’s most famous novel. This uniquely nondogmatic approach invites debate and discussion, something Briann Greenfield, the executive director of the Stowe Center, emphasized was essential to the foundation’s work, which aims to use Stowe’s work to engage with current issues.

Even from the outside, Stowe’s house felt familiar. Walking through the parlor and dining room, which are largely decorated with furniture that belonged to the writer, my oldest son insisted we had been there before. The familiarity made it easy to assume we knew the lives lived within those walls—bowed heads at the dinner table followed by piano music in the parlor.

While some version of that might be accurate, it’s equally true that the ordinary lifestyle of the Stowes belied their radical politics. Harriet was the seventh of 13 children in a family of prominent ministers who preached more than just fire and brimstone. Her father, Lyman Beecher, and brother, Henry Ward Beecher, were prominent abolitionists. Stowe would outdo them all with her 1852 publication of Uncle Tom’s Cabin.

Hartford, Connecticut

The Harriet Beecher Stowe Center: The writer’s longtime residence is the perfect place to consider her complicated legacy. The center’s engagement with issues of race and justice ensures the house is more than just a testament to the past.

The Mark Twain House & Museum: This stunning neo-Gothic mansion offers an intimate glimpse into Twain’s personal and public life and features an adjoining museum showcasing his writings.

As we explored Twain’s house, I explained how George Griffin, a formerly enslaved Black man, had been the butler and perhaps the inspiration for Jim, the escaped slave in Adventures of Huckleberry Finn.

Unsurprisingly, Twain’s house has been immaculately preserved with original objects from the Clemens family. The painting named for Emmeline Grangerford, a character from Huckleberry Finn, hangs above the fireplace, alongside the Clemenses’ carved wood “angel bed,” made famous during a newspaper interview in it.

Concord, Massachusetts

The Orchard House: Here, the vibrant spirit of Louisa May and her sisters is most acutely felt, serving as the inspiration for Little Women.

Twain’s estate is a marvel of American Gothic architecture—an elaborate blend intended to overwhelm with its scale and detail, demonstrating how he often entertained visitors with his humor, as reflected in the walls adorned with his famous one-liners.

Before entering Orchard House, Jan Turnquist, the executive director, encouraged us to visualize Louisa May and her sisters performing plays in the living room or running through the garden. It was easy to picture, given the careful preservation of the objects that the Alcotts lived with, including the desk where Louisa May wrote.

For anyone who has read Alcott, walking through her home feels like both a memory and an act of imagination, embodying Margaret’s declaration in Little Women: “I know, by experience, how much genuine happiness can be had in a plain little house.”

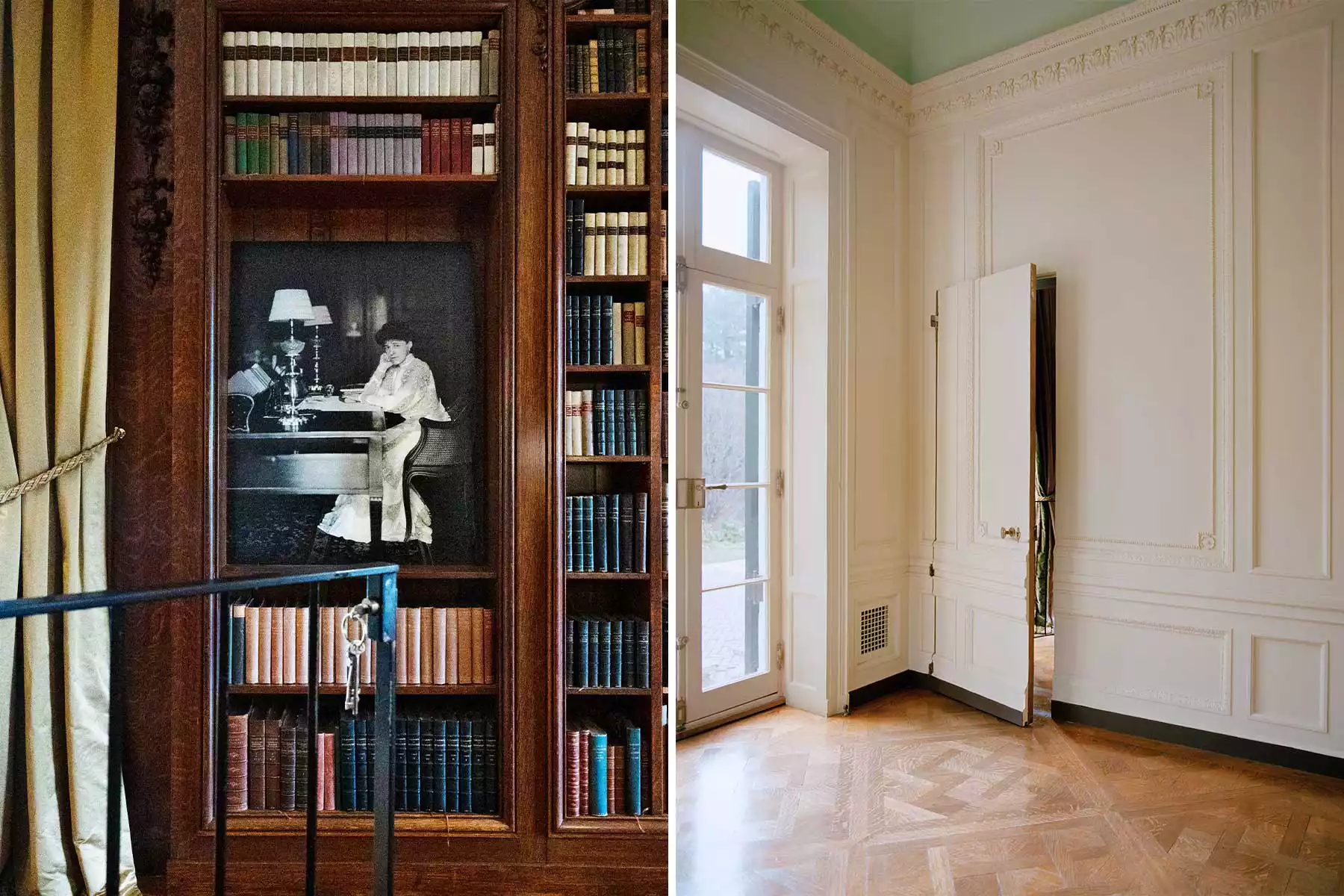

When we arrived at the Mount the next morning, our children ran off to explore the garden while reflecting on Wharton’s resilience and artistry. Although many objects belonging to Wharton are not present, the beautifully preserved library showcases her vast collection of books, and the house itself, noted for its architectural symmetry and secret doors, offers an elegant tribute to her vision.

As we reached the conclusion of our literary pilgrimage, our hopes of spotting ghosts transformed into a deeper appreciation of the writers we had encountered along the way. Each home left an indelible mark on our journey through literary New England, merging the past and present in a rich tapestry of culture and creativity.